This post will look better in a browser.

Things are changing. The students are gone, and the apprentices have packed up their desks. The shop’s space has been returned to a place for work.

All the wood in the shop had to be re-stacked to access material we would need for our next projects: a minka restoration that would become our new schoolhouse, and two timber frames that would become student dormitories.

When it was time to move the wood, Jon’s calm eyes shifted sharply; his energy became wild. His momentum was undeniable and contagious as he moved logs with a seemingly reckless pace. The apprentices joined in.

I was summoned to help move a chestnut log, but as soon as I felt the weight of the tree even partially, I knew my back would not survive it. When I told them I would not be able to help on this log, they just moved it themselves, one man down. They loaded a truck with lumber for the minka project, and restacked everything in the space the apprentices had cleared the month before.

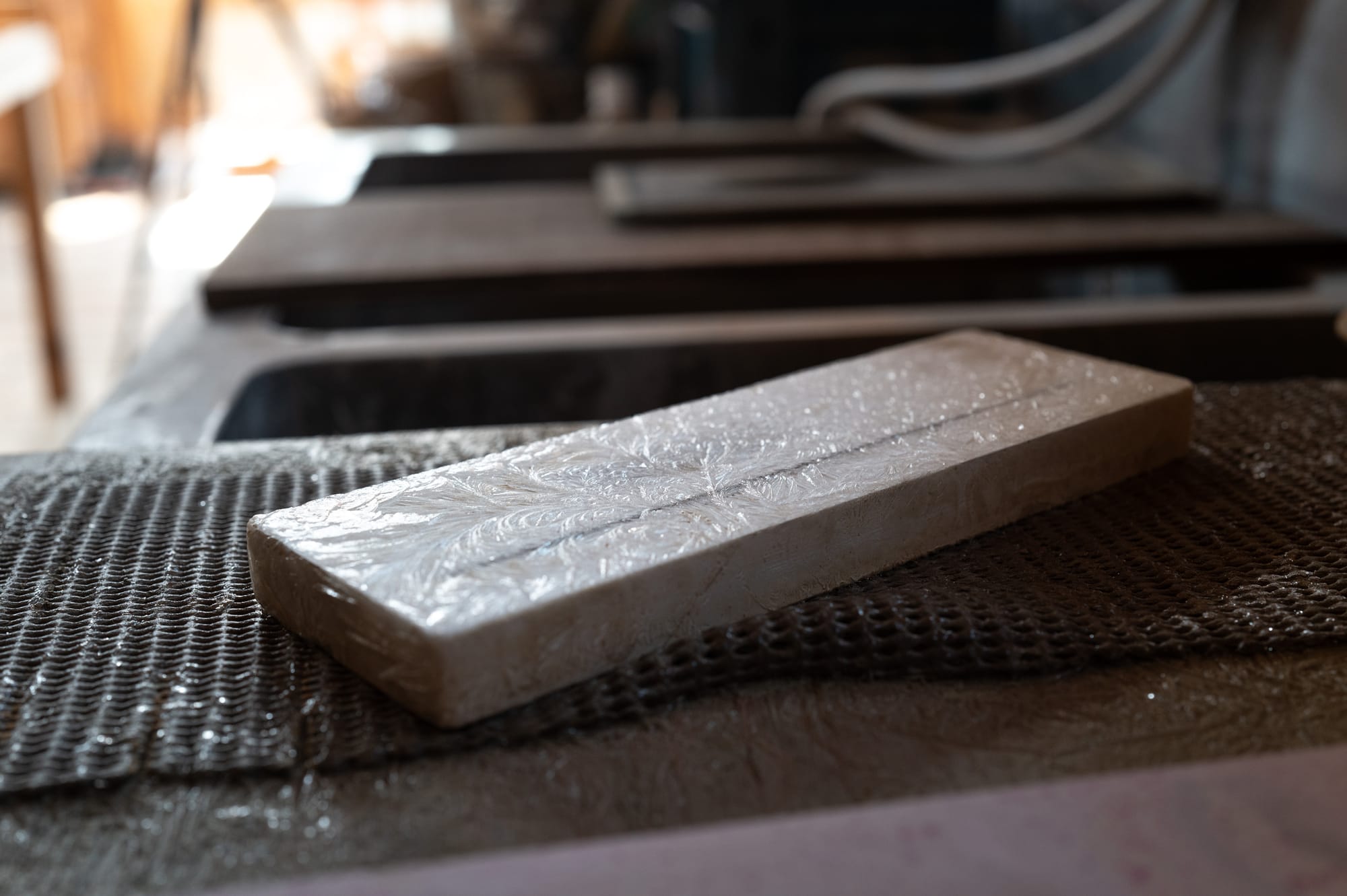

I volunteered to sharpen the chisels and bits for the beam mortising machines we would be using.

The bits were beat up and rusty, despite being stored in motor oil. A soap bath was prepared for the bits and stones to cut the oil.

Using diamond resin stones and a grinding cone in a drill, I removed rust from the outside after raising a burr on the inside.

The 15mm cut like a laser, but I couldn’t quite get one of the 30mm bits to work well. It was definitely wedging into the workpiece and slowing progress.

Related: On sharpening and tuning mortising machines

We worked on putting notches in floating keyaki tenons. In amateur work, it's often taught to safely rough with a heavy chisel, and then pare away to split the line. In production work, it was only possible to go fast enough by attempting to split the line with the chisel and hammer, to keeping paring to a minimum.

Destroying the duality between rough and finish work was a common theme at Somakosha. We were expected to be as fast and clean with all our tools, blasting through material to sub-millimeter precision, in all our operations.

Often, that meant bringing your work to the brink of ruin with a fast and aggressive tool, but not destroying our lines. Then, doing this again and again, swiftly. The greatest benefit to a professional environment is the scale through which to achieve a great deal of practice.

Before we could cut, the apprentices studied the work Ta-chan had spent long days and nights laying out.

As the apprentices worked on this basic frame, Ken-san continued to lay out round posts for a Sukiya-style fence. Of note is a jig used to hold a router over a round to rough mortises, which also allows for the workpiece to be spun 180 degrees to mortise the other side. (This is an invention by Jon Stollenmeyer.) The rest was by feel and sensitivity.

Work is punctuated by frequent breaks, which seem like a good safeguard against mistakes or injuries from fatigue.

At lunch, I would often walk with Ken-san 5 minutes away, past the bridge and general store, to Kubo-farm, where we would eat together.

The apprentices generally cooked at the shop.

But would allow themselves a meal at Kubo on particularly cold or hard work days.

Before we could get to work, some apprentices prepared tools, while others were assigned to finish breaking down scrap wood.

Some apprentices worked steadily on their tasks; others ran hot and cold, with a lot of passion. The less glamorous tasks would challenge apprentice morale at times. When one apprentice complained that it was unfair that others got to do more interesting work, he was told that the faster he finished this work, the sooner he could join them.

It became apparent that tasks were an essential part of keeping the company running, and also refined the spirit of the apprentices, keeping them humble, hungry, and forced them to learn how to focus when the work felt less interesting.

It was also clear that any task completed with full focus, spirit, and attentiveness would be noticed by bosses, no matter how seemingly low. This was the way forward, but it was not always easy for the younger staff to see this.

The perfect Fall weather continued to descend into something else. Soon, it would be time to cut.

Subscribe