Apologies for the image quality in this post. I'm testing out some glasses with cameras in them to help me stay more focused when working. The technology isn't there yet.

Temperatures continue to drop, and most days stay around freezing. Sharpening stones cracked after being left overnight in bins of water by apprentices; snow flurries drift onto workpieces mid-cut. Layers of clothing grew deep and stayed deep as work continued entirely outdoors or in the open shop. We kept warm by continuously working and sipping coffee from the vending machine across the street.

Site work at the Somakosha school dormitory continued. Yoko continued to cut beams on site.

At the shop, Lintels were milled, grooved, and installed by Ta-chan. Ashwin and Clark continued to install bamboo for the plaster.

When Ash installed some looser than ideal by accident, Ta-chan offered some gentle encouragement by saying something like, "loose work, loose life, loose everything." (This is a paraphrasing, I only heard second hand.) Ash redoubled his effort.

After the roof work last week, Jon pulled me into milling some parts for the Sukiya fence that Ken-san had been working on. The fence has an angled support, scribed to the round posts.

To secure the post to the supports, pegged nuki would slot into the tenons. The top nuki would have an expanded, mushroom-shaped head scribed to the brace. The lower ones were rectiliner but inserted at an angle to the work piece. Both would be pegged.

These would be milled from chestnut, along with some horizontal pieces for the bottom of the fence that would be hewed.

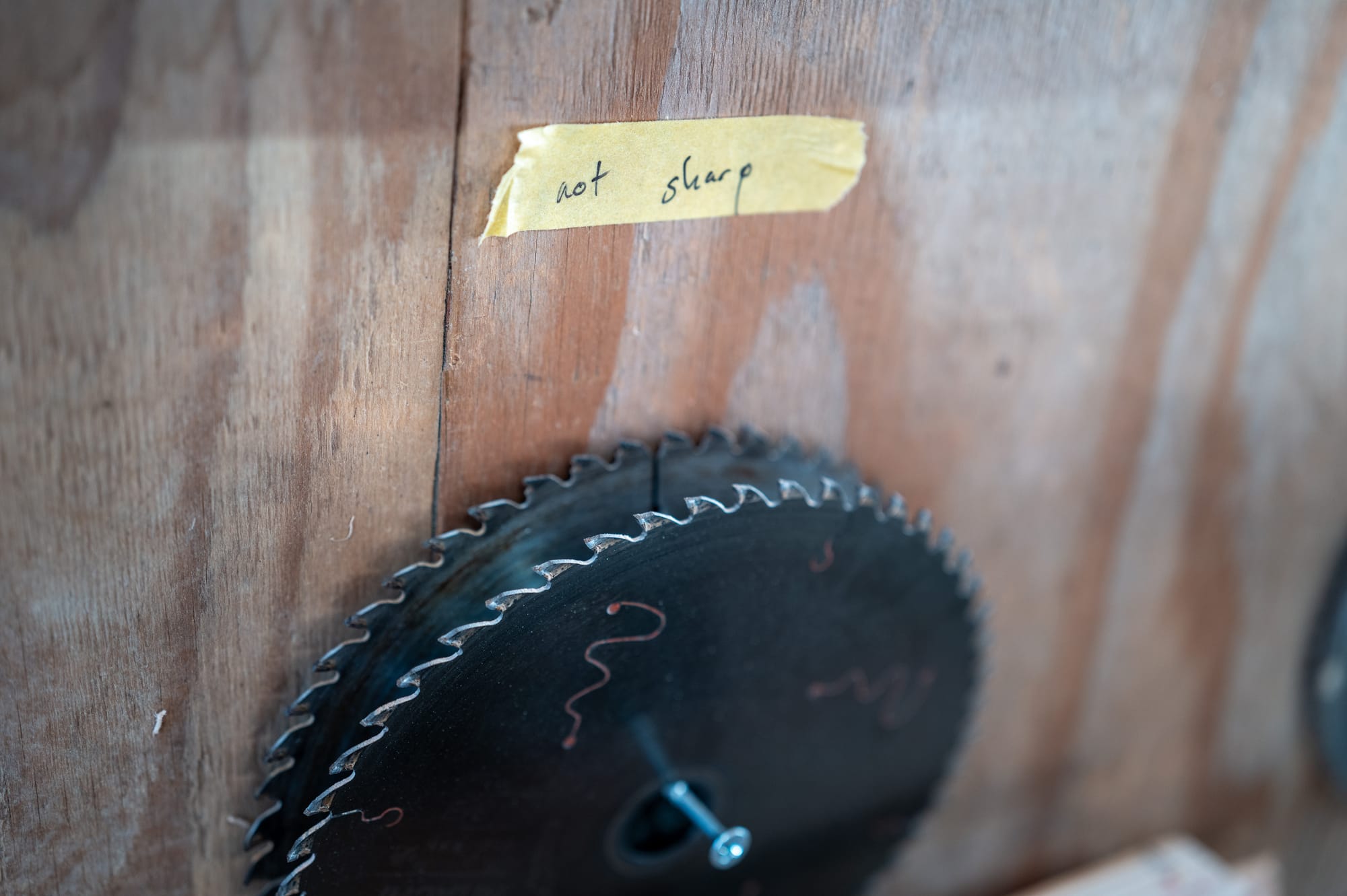

Wood would ideally be from the same tree, matched, with enough width after sap wood was removed. Roughing would be accomplished by circular saw, bandsaw, jointer and planer.

It would be my first time selecting and orienting wood for a project, and milling for production. The task is a difficult one, and I am thankful to have spent a few weeks selecting wood for various projects, with Yann Giguere, my first teacher. I sent him a note giving my thanks. Factoring in all the different elements, including predicting which way the wood will move over time as it dries, or what side looks or weathers better, and positioning the most ideal of your stock into the right position, is an extremely fun and challenging act.

What had to be done here was take a bunch of checked chestnut logs and pull out a few 400mm pieces, about 60x100mm in width/height. Of course, the checks had to be removed as much as possible, or left in spots that would be removed as we cut our joinery. In the end, it took time, and there was much wastage.

Sukiya carpentry emphasizes this process of selection and orientation, and the cost of this work is high because of the time and the amount of wood that ends up being discarded or reused in different projects with less stringent requirements. Order overages in material quantities is much higher in this kind of work.

Some more horizontal pieces from sugi needed to be milled from door stock, 1-2 meters in length, of various widths from sugi door stock.

Often, a piece would fall just short of our requirement to hit 90mm after milling

The sugi horizontal pieces were chosen out and cut, but some were too short. So, we dug deeper into the tall stack until we found some that needed to be resawed at an angle so the grain ran straighter. A line was snapped so the circular saw could be run freehand along it.

Being any part of a fence project like this is a gift for someone with as little professional experience as I have. I would guess most apprentices might wait years or more than half a decade to participate in a sukiya project like this one. To be clear, I haven't earned this opportunity, and I'll try to live up to the responsibilities and opportunties I'm being given.

While I milled small chestnut pieces, Jon, Sakaguchi san and his son Ayumu kun worked on milling extra parts of the Somakosha school minka restoration.

Many parts in the building were rotten and the project was difficult. Sakaguchi san was moving the timbers with power, and it shocked me to learn he had an injury on a jobsite a few months ago where he broke both his heels in a fall.

Yet, here he was maneuvering and resawing timbers with the strength of a bull. Besides their obvious power and grace at work, the father-son team carried a silent understanding of what would need to be done together, a kindness, and quiet dignity that showed in every movement, word and smile.

In between my tasks, I would check in on them, and I was surprised to see they filled the dust collector I had just empied in less than 30 minutes, so they dumped the bag on the floor.

I scrambled to clear the chips as they could cause a carpenter to slip, and I could barely keep up with their pace.

I never clean slowly. Cleaning with vigor engages the senses and mind making me feel alive; I am beginning to enjoy it as much as wood craft itself. In both ways we are removing material to reveal a more ideal form of something, whether it is a space or work piece.

Through the process, I feel the same sense of accomplishment and contribution to the project, the company, the client, and the world at large.

By evening, I could feel my mind and body becoming numb from the cold and exertion. Focus was eluding me, with fingers centimeters from spinning blades.

It was time to step away from the jointer, the machine known to bite many daydreaming apprentices, go home and drink a cold beer in a hot bath.

Subscribe